In psychology, there is an interesting concept called “locus of control”. It was first established by psychologist Julian B. Rotter through his work on social learning in the 1950s and ’60s¹. And it still is one of the most researched notions in the field today².

Locus of control – often abbreviated as LOC – has to do with personal perceptions around things that you can and cannot control in your life. It’s one of those concepts that can be of great help in making life choices. Especially when you’re discovering what you want and trying to take charge of the direction your life is taking.

This month’s edition of Maxand’s Insights focuses on what locus of control is and how you can use it to your best advantage.

1. What is locus of control?

Locus of control refers to the degree to which people believe they can control the outcomes of events in their lives. If you have a so-called internal locus of control, you believe that these outcomes – such as success and failure – lie within your own control. If you have a so-called external locus of control, you believe that these outcomes are controlled by forces outside of yourself. Forces like fate, luck, other people or a higher power.

You may, for example, feel that if you only practice hard enough you can become absolutely anything you want (internal locus of control). Or you may believe that the social group you happen to be born into fully determines what you can become in life (external locus of control).

Or let’s take something completely different: a belief around whether you can control certain health outcomes. For example, you may believe that what you choose to eat doesn’t have any major impact on the physical processes in your brain and how you feel (external locus of control).

There are a few important things to note:

- Locus of control refers to a perception of ourselves and the world around us. As such it is subjective, not an absolute truth.

- Locus of control can refer to a belief you have in general about whether or not you have control over outcomes in your life. But it can also refer to a belief you have control with regards to a specific situation. As such, you’re likely to have a different locus of control for different circumstances. You may, for example, feel you have control over how well you do in your current job. But not about whether you’ll be able to get the job you’d like to have next. Or vice versa …

2. Where do we get our locus of control (general and specific)?

As we grow up and go through life, we each have our own unique experiences in our own contexts and with our own physical and mental make-up. Through these experiences, we learn about what is or isn’t within our own control.

These lessons are important, as they help us navigate and survive in the specific circumstances we’re in. As such, they aren’t right or wrong in any absolute sense. Instead, they’re simply dependent on things like the physical conditions and climate you live in, the social environment and culture around you, et cetera.

Yet, when you’re on a quest to discover what you want and take steps towards that, it helps to remember that what we learn is often not a hard fact. Locus of control is a belief we have. A perception. As said, it’s subjective and it isn’t necessarily 100% true all of the time.

In our three earlier examples:

- “If you practice hard enough you can become anything you want.” => Although this belief is great for self-confidence, it’s objectively not true. Some things will always remain beyond our reach or control.

- “It doesn’t matter what you do. The group you happen to be born into fully determines what you can become in life.” => While the group you’re born in may be a very important factor in determining what you can become, this doesn’t necessarily mean that this remains the same over time. Or that unique or well-developed individual skills can’t make a difference at all.

- “What I choose to eat has no major impact on the physical processes in my brain and how I feel.” This is one of those instances where new scientific discoveries change beliefs we may have had. In this particular health-outcome example, experts now increasingly find that what you eat actually has a very strong relationship with things that are physically happening in your brain as well as with how you feel.³

So to conclude, locus of control really is subjective and may or may not prove to (fully) reflect actual, objective reality.

3. How can this help you in discovering what you want and taking charge of the direction your life is taking?

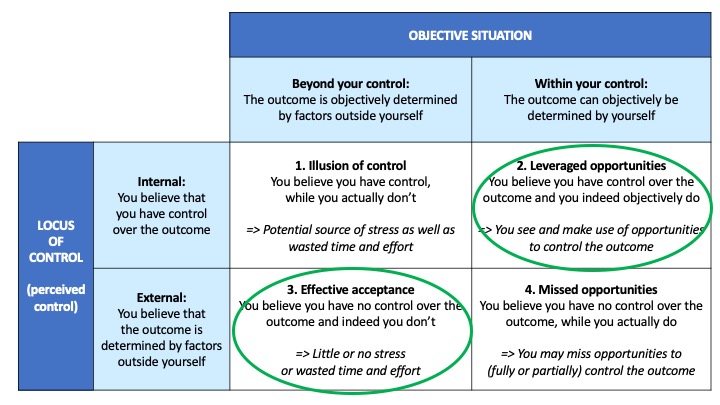

The concept of locus of control can help you avoid pitfalls and create more opportunities for yourself. Contrasted with the objective situation, it gives you a tool to examine your own beliefs closely as to what lies within or beyond your control. Let me introduce table 1.

A. Introduction

Give yourself a moment to examine the table.

To start with, there are two main dimensions in the dark blue boxes. In the left vertical column, you find “locus of control” which – as you now know – refers to a subjective perception of control. Next, in the top horizontal line, you find the “objective situation”. Each of these two dark blue dimensions is then subdivided into 2 sub-dimensions in the light blue boxes.

For locus of control (perceived control):

- internal: you believe that you have control over a certain outcome

- external: you believe that the outcome is determined by factors outside yourself (fate, luck, other people, a higher power, etc.)

For the objective situation:

- beyond your control: the outcome is objectively determined by factors outside yourself

- within your control: the outcome can objectively be controlled by yourself

Note that it can be difficult to determine if something is objectively really within or beyond your control. Don’t let yourself get too distracted by that. The point of the model is not to seek absolute truths, but to help you challenge your own beliefs in what is within and beyond your control.

B. Contrasting perceived versus objective control

Of course, there are now two ways in which your perception can differ from the objective situation.

- The first is when you think you have control over a certain outcome, while in fact you don’t. This leads to an “illusion of control” and potentially wasted time, effort and resources (number 1 in the table).

- Secondly, you may think you have no control over a certain outcome, while in fact you partially or even fully have control. This could lead to “missed opportunities”, as you fail to see and take advantage of possibilities that present themselves (number 4 in the table).

Similarly, there are two ways in which your perception actually coincides with the objective situation.

- The first is when you think you have control over a certain outcome and this is indeed the case. This leads to “leveraged opportunities”, as you’re likely to see and make use of possibilities that come along (number 2 in the table).

- And secondly, when you think you have no control over a certain outcome and indeed you don’t. This leads to “effective acceptance” and very little stress or wasted time, energy or resources (number 3 in the table).

When you’re trying to discover what you want and take charge of the direction your life is taking, the challenge is to really critically reflect on whether your perceptions match reality and then act accordingly. You want to make sure that your perceptions match reality as much as possible (the green circles in the table).

C. Using the table: A practical approach

A practical way to use the table is as follows (for those of you who are using last month’s stepwise method, please also read Part 4 below).

- As you’re discovering what you want and working towards that, make a list of the things that you think are needed along the way. For example, actions you’d need to take, phases you need to go through, people you need to involve somehow, resources you might need et cetera.

List these items in 2 columns: one column with the items you believe are within your control and another column with the items you believe are beyond your control.

- For each of the items that you believe to be within your control, ask yourself very critically to what extent they are indeed within your control.

Perhaps you have to conclude – upon reflection – that some things are actually not within your control. If so, think about what would be needed for you to accept that factors outside yourself determine the outcome instead. In addition, if you’ve been spending time, energy or resources on those particular outcomes, think about what would be needed for you to stop doing so and let go.

Example:

An example would be when you’ve been trying in vain to get the approval and support a self-oriented friend while your new direction in life is to his/her disadvantage. What would be needed for you to accept that you cannot control this? What would be needed for you to stop investing time and energy? Answers could range from inner acceptance that you may lose the friendship, to letting your friend know that you’d hate to lose him/her but that you have to go your own way, to finding new friends who do support you, et cetera.

- Similarly, for each of the items that you believe to be beyond your control, ask yourself very critically to what extent they are indeed beyond your control.

If – upon reflection – you have to conclude that some things are actually partially or fully within your control, think about what would be needed for you to start taking steps in those areas. Really challenge yourself and try to identify more opportunities to your advantage!

Example:

You may, for instance, have learned that the only way to make steps on the career-ladder in your specific context is to be related to powerful people. This lesson can be very helpful in determining how you want to go about developing your relationships. But it may also lead to you spending less or no time on developing specific skills or getting a degree. Even if you’d have the opportunity to do so. This could considerably weaken your future independence. What would be needed for you to also maintain your own development? What areas of development would be effective and efficient for you to get involved in? How can you make it count? Et cetera …

4. Note for those of you who’re using last month’s step-wise method …

If you’re using last month’s step-wise method, you can use the model in table 1 above as a reflection tool to further explore if your identified items lie within or beyond your control (phase 2, part B in week 5).

Of course, the stepwise method includes a more nuanced approach that includes not only things that are within and beyond your control, but also things that you may be able to influence, albeit not fully control. This dimension was not added in the current article to avoid overcomplicating the model.

There are a few ways around this, so have a look what works best for you. You could treat the items in your “within influence” cluster as combinations of things that you can and cannot control, and list the different sub-elements accordingly. Alternatively, you could treat your “within influence” items as things that are within your control in the current model, although perhaps not fully (e.g. partial control). Or find another way that meets your needs. Be pragmatic. No need to overcomplicate things.

The main point is to really take a step back and reflect critically where you might miss opportunities and where you could create more. Adjust your circles accordingly.

Footnotes

1. See for the original work by Julian B. Rotter:

- Rotter, J.B. (1954). Social Learning and Clinical Psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall.

- Rotter, J.B. (1996). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80 (whole issue 609).

2. There has been a massive array of research in very, very many different aspects of life across the world. If you’d like to get a sense of what’s been going on in the field, search for “locus of control” in for example Google Scholar at https://scholar.google.com. Or, if you’re interested in a more structured overview, let me refer you to the following book.

- Reich, J.W., & Infurna, F.J. (Eds.) (2017). Perceived Control: Theory, Research, and Practice in the First 50 Years. New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

3. A lot of research is currently undertaken into the way brain functioning and mental health is related to food and processes in our digestive tract. Have a look at, for example, the following TED talks for a general impression.

- Neuroscientist Sandrine Thuret on “You can grow new brain cells. Here’s how”. TED@BCG London (June 2015).

- Doctor Giulia Enders on the “The surprisingly charming science of your gut”. TEDxDanubia (May 2017).

If you find subtitles helpful with the videos, then just click the appropriate language or alternatively select “Captions” under the “CC” sign in the bottom right of your screen.

If you’d like to know more about the basic functioning of the brain, you may also want to have a look at the Maxand articles “Meet your biggest ally: Your brain” and “Too much to learn? Here’s what to do“.