So you’re on the Internet looking for some inspiration in discovering what you want. Perhaps you’re from Malaysia or Brazil. Or from the USA, Austria, Ghana, Kazakhstan or China. Or who knows? You’ve landed on this page written by a Dutch person. Later, you might visit a site by someone from Canada, India or another part of the world.

But to what extent does that make sense? In something as personal as discovering what you want, can you take what was written by someone from another culture and apply it to your own situation? It’s an intriguing question. With even more intriguing answers.

1. Why bother about culture?

When we were young, all of us were socialised in some particular culture or mix of cultures. We’ve learned about the way people live together in our part of the world and adopted some of the underlying assumptions, norms, values, beliefs and attitudes. We all view the world through our own cultural filters, our own pair of proverbial glasses if you will. Some we are aware of. But I dare say, of many we are not.

Encountering cultural filters different from your own is one of the most effective ways to become more aware of them. And this is important! Because discovering what you want has a great deal to do with discovering more about yourself. By understanding yourself better – including the way you’ve come to view the world – you can increase your range of conscious choice in how you want to lead your life.

But when you go online looking for inspiration in discovering what you want, you may not be aware of the cultural filters you’re using to begin with. And the authors (bloggers, vloggers, tweeters etc) you meet online may not be conscious of theirs. Plenty of room for misunderstanding! Resulting in several risks:

- You might unintentionally dismiss something that could actually be of value to you.

- Conversely, you might think that some concepts and ideas represent the latest globally applicable scientific insights. While in fact they only represent a specific culturally determined norm.

- You might adopt concepts and ideas without being conscious of their cultural context. This could result in effects or consequences you did not see coming.

- You might end up worrying or being stressed about things that are ‘only’ culturally determined. Some of those may not necessarily need to be sources of worry or stress.

So when using sources from other cultures, the question becomes how to uncover hidden insights while avoiding the pitfalls. Unfortunately, this is not a case of ‘just do this, then do that and then everything will be clear.’ Understanding cultural differences isn’t like solving a mathematical formula with one single right answer.

This Month’s Insight will be the first of a number of articles on the topic, that I’ll add to over time. Today, I’d like to start with some of the basics:

- A quick introduction to culture.

- A deep-dive into a cultural filter that is very fundamental in discovering what you want: the way we view the “I” in the question “What do I want?”

- Practical tips on how to approach websites, articles etc written by authors from another culture.

2. A quick introduction

A. What is culture?

Let’s take a step back for a second and look at ourselves. As a biological species you could say we’re perhaps a little bit pathetic. We don’t come with sharp fangs, slashing claws or smart camouflage. We don’t have a terrible growl to scare off predators. And we don’t have much fur to keep ourselves warm in colder climates. What has kept us alive and made us thrive is that we’ve found clever ways to collaborate with others.

Culture refers to the way a group of people – over time – have learned to live and work together. A key thing to understand is that cultures developed in response to survival needs and historical developments. Those are of course different across the various parts of the world. But even with similar survival challenges and historical developments, different communities have come up with different solutions and ways to give meaning to life.

And so cultures came to vary across the world. They made sense at the time they developed. Even if some of their characteristics appear strange or may no longer make sense today.

Some aspects of culture are very visible, such as language, food, buildings and ceremonies. Other aspects of culture are less directly visible, such as communication styles, concepts of friendship and handling of time. It’s not that easy to really get a sense of them unless you spend some time interacting with people from that culture.

The cultural filters through which we see the world constitute a less visible part of culture. We’re often not quite conscious of them, until we start noticing particular consequences or differences with others.

B. But note …

Before I say anything more about culture, let me first emphasise we are all more than our cultures. We are also our own individual selves. With our own specific DNA, personality and experiences, and our own individual norms, values, beliefs and attitudes.

Also note that any overall description of a culture will by definition fail to do justice to its richness and complexity. Whenever I offer an general description, it is only meant to show overall trends or patterns. It is not intended to suggest that therefore everyone from that particular culture will act in that particular way. Nor that therefore cultural characteristics will be completely the same in all parts of a particular region.

3. Deep-dive into a very fundamental cultural filter: the “I” in the question “What do I want?”

Given our interdependency with others, every society has had to find a way to balance the needs, norms, values, beliefs etc of individuals with those of the wider community. It won’t surprise you that different societies have come up with different ways of doing so. They vary greatly in the extent to which the individual is seen as an independent entity in itself or as part of a larger group.

A. To illustrate: Country scores in “Individualism versus Collectivism”

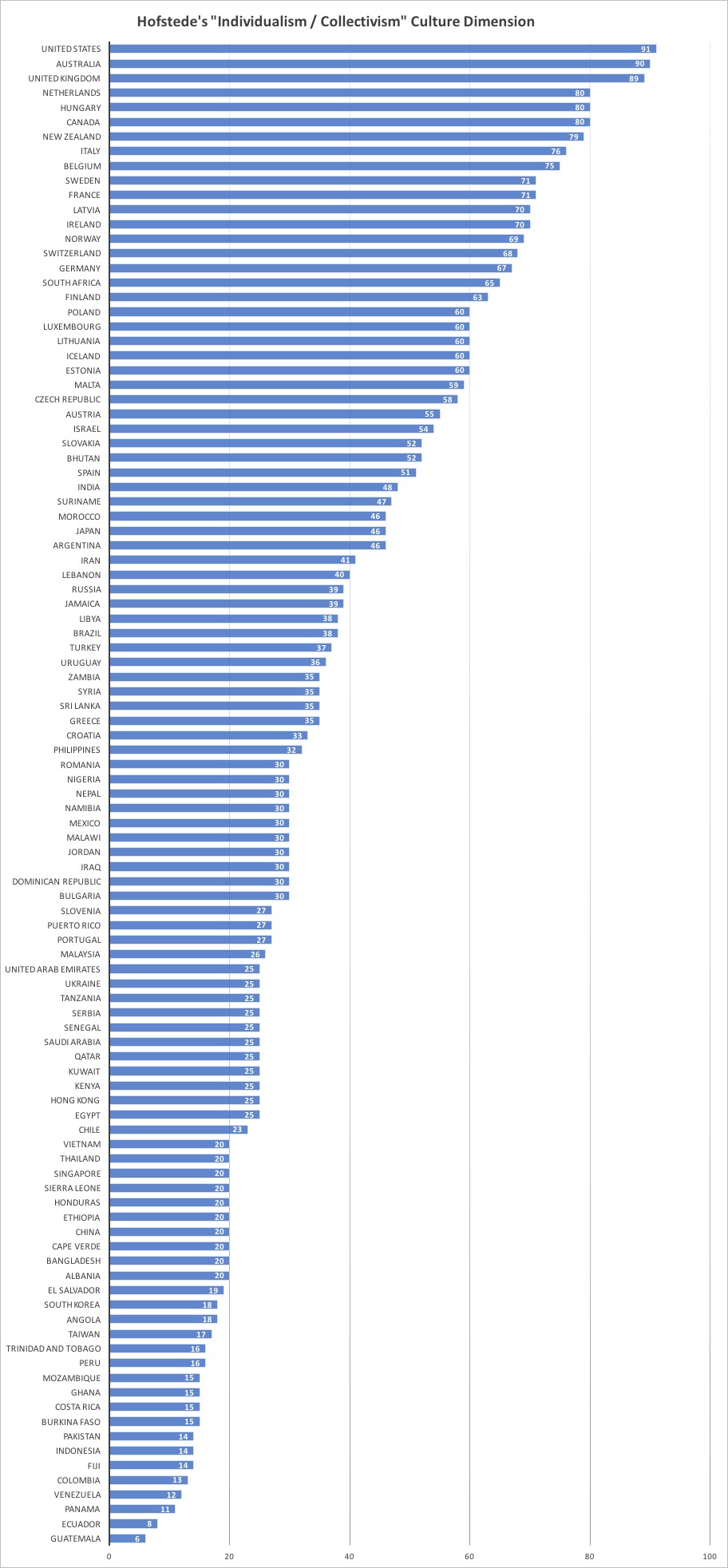

Let me illustrate the different perspectives by using the so-called 6-D Framework developed by Social Psychologist Geert Hofstede¹. Hofstede has found 6 Culture Dimensions that help us identify key characteristics of country cultures. One of the Culture Dimensions – called “Individualism versus Collectivism” – reflects the way the individual is viewed and defined.

As with all models and research, the 6-D Framework and underlying research have their limitations². However, I quite like using them for several different reasons:

- Given Hofstede’s definitions, the “Individualism versus Collectivism” Dimension provides valuable insights that are relevant in discovering what you want.

- Data is available for more than 100 countries.

- The main six Culture Dimensions appear statistically valid and reliable across decades of research.

- A free online tool was developed to explore cultural differences yourself (see the Hofstede Insights’ Country Comparison Tool).

Graph 1 below gives you all available scores by country. In Hofstede’s definition, countries that score high are considered “Individualistic”. If you are from a country like that:

- You are probably used to a society that maintains only a limited amount of interdependency between individuals.

- You tend to see a preference for loosely-knit social networks around you in which individuals are expected to take care only of themselves and their immediate families.

- You likely define yourself more in terms of “I” or attributes that belong to you specifically (your job, your skills, your roles in life etc).

Conversely, countries that score low are considered “Collectivistic”. If you are from a country like that:

- You are probably used to a society that maintains greater interdependency between individuals with a preference for more tightly-knit social networks.

- You tend to see around you that individuals can expect their relatives (or members of other particular in-groups they are part of) to look after them in exchange for their loyalty. The ways to show loyalty as well as the ways to take care of others in the in-group may take a whole range of different forms.

- You likely define yourself more in terms of “we”, and in terms of the (attributes of) groups you are part of.

Now take a moment to scan through the list³. Some scores may resonate with you quickly. Other scores may be more surprising. See if you recognise the results for the culture in your own and other countries. If you’d like to have a more detailed interpretation, just type the country’s name in the Country Comparison Tool.

B. What does this mean in terms of discovering what you want?

Now, Hofstede focused on culture and work values, not on discovering what you want. But – very cautiously – we could develop an impression of cultural differences in this area.

For “Individualistic” countries one could imagine how:

- Individuals are allowed (and expected) to decide how to live their lives based on their own wishes and needs. Any restrictions are likely only posed by the needs of their immediate families and formal rules.

- Not leading a life the way someone would want based on his/her own needs and wishes, is seen as the responsibility of the individual him/herself. Trying to assign responsibility for such a situation to someone or something else is frowned upon. Unless there are really aggravating circumstances.

- Stress occurs primarily if people are not sure what they want based on their own needs and wishes. Or – when they do know – from not being able to arrange their lives accordingly. This could be because of personal circumstances, the needs of their immediate families or formal rules.

Conversely, for “Collectivistic” countries one could imagine how:

- Individuals are aware of their own needs and wishes, but tend to be led by their commitment to the larger in-groups of which they are part. Either in terms of continuing to show their loyalty to those groups or in taking care of other members of those groups.

- Not leading a life the way someone would want based on his/her own needs and wishes, is seen as something that happens but that is usually meaningful.

- Stress for individuals results primarily if an in-group does not or cannot return their loyalty in a meaningful way. Stress for an in-group results primarily if an individual tries to lead his/her life without regard for the groups s/he is part of.

People at the two extremes will have very different ideas about finding answers to the question “What do I want?”! And they are likely to use very different words when talking about it.

Note that there is no right or wrong here. It’s just different cultures having developed in different ways with each having their own characteristics.

4. So how to approach this?

When you find a website, article etc written by someone from another culture:

- Dive right into it with lots of attention! Be curious. Postpone your judgment. Just take everything in first.

- Pay close attention to the words the author uses and the ideas s/he launches. Try to get a sense of how s/he views the individual, the “I” in “What do I want?”. If you know where the author is from, consider checking Hofstede’s research results as well³. But note again that an author may or may not act in line with the culture s/he’s from.

- Pay attention to the words and ideas that appeal to you as well as those you dislike. What does this tell you about yourself? How have you come to see things like this? Could you see things differently?

- For your own culture, try to get a good sense of how the individual is viewed vis-à-vis the larger community. Why was it logical that it developed this way over time? To what extent have you yourself adopted this same way of looking at the individual?

- If you yourself look at the individual differently than other people in your culture, what are the differences? What does this mean for you?

- Look at the things that tend to make you feel stressed or worried in discovering what you want. What part of that is culturally determined? What does this tell you?

Examining websites, articles etc from other cultures this way generates additional ideas and personal insights. Ideas and insights that can support you in making more conscious choices with increased confidence. Even if the choices you end up making are the same ones you would otherwise have made …

Footnotes

1. Geert Hofstede’s first well-known peer-reviewed publication on the topic, titled “Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values”, was issued in December 1983. It was published in the Administrative Science Quarterly of Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University (28 (4): 625–629). Many publications followed, including work with his son Gert Jan Hofstede, who is a Population Biologist and professor of Artificial Sociality. Also see www.geerthofstede.com.

2. The work done by Geert Hofstede has been immensely valuable in exploring differences between cultures. However, when working with the data, there are a number of limitations to be considered.

- The model reflects a number of cultural dimensions meant to discriminate a number of key characteristics on the basis of which cultures can be compared. They are – by definition – a simplification of reality.

- Data was gathered across a great many countries (more than half of the current number). However, data could not be gathered in all countries. Reasons for that ranged from conflict situations in some countries to new countries being created after the main studies.

- The Culture Dimensions appear statistically valid and reliable. However, by definition, their interpretation at the more detailed level of individual cultures remains a challenge.

- As the research focused on culture and work values, its focus was on people in a work situation. The extent to which the results reflect culture within the broader community is sometimes unclear.

- Results concern entire countries without allowing for sometimes large regional differences. This can be a specific challenge in interpreting the results.

- The bulk of the research took place some time ago in the 70s, 80s and 90s, although research projects are ongoing today. When using the data, one should keep in mind that cultures change continuously.

3. Perhaps no data is available for your country (yet). If so, see if you can use the definitions to get a sense of how your country might score.

Interested in other articles? Have a look at:

- Discovering what you want: Small & simple things to start with today

- Why ‘not knowing what you want’ is so very normal