Maxand’s origin

I never knew my grandfather. But whenever I tried to think of the right scope and a name for this website, I somehow ended up thinking of him. A man who faced daunting dilemmas, but who remained steadfast in what he wanted. A man whose decisions still echo through in my life today. His name inspired the name Maxand.

Max Ferdinand Bernecker …

What I know of him comes from stories I’ve heard in the family and from an album my aunt Yvonne wrote about the life of her mother, my grandmother.

He was born in the colonial era, on 16 February 1911. His family lived in the city of Makassar on the island of Celebes in the former Dutch Indies (currently the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia). The blood of early German/Swiss settlers ran through his veins alongside that of the European and Asian women they had married.

As a young adult, he rode a flaming red Harley Davidson to his part-time job at a racehorse stable, that helped him pay for his university studies. He had decided he wanted to become a veterinarian. Unfazed by the fact that – in these times of worldwide recession – it made much more sense to choose safety in for instance banking or government employment.

He met my grandmother when she was 17. She was an intelligent and beautiful young lady … and very independent. Unsure of her feelings, she kept my grandfather at bay for years. But he very patiently and gently kept on courting her. And in the end, his perseverance paid off. They married soon after he graduated. Seven years passed between the moment he first fell in love with her and their wedding. He never faltered.

Blissful times on Sumatra

They married on 5 May 1938, she 24 and he 27. A few days after the wedding, they took all their belongings, said goodbye to their families and traveled to Padang on the island of Sumatra. Their new home would be in Fort de Kock, where my grandfather was appointed the new Director of the zoo.

My grandmother used to tell wonderful stories of the years they spent there. Fort de Kock was a friendly city, sprawling gently around two high hills. The zoo was situated on one of the hills, the remnants of the old Dutch Fort “De Kock” on the other. From the hills they could look out over the city below and gaze over the thick green foliage of the jungle stretching far beyond the horizon, where the Singgalan and Marapi volcanos loomed large.

When night fell, they could hear wild monkeys howling in the trees or skirmish on the roof. The roars of the tigers in the zoo would sometimes be answered by the roar of a wild tiger, hidden in the dark Sumatran jungle. Soft tunes of a suling, a flute, would float on the chirping of crickets and cicadas. My grandmother particularly liked tending to her rose garden and enjoyed learning to cook local dishes. When she wasn’t looking after their newborn children …

My grandfather, meanwhile, was making the most of his time there. His work as Director included managing the butcheries behind the zoo, where the meat was cut for the zoo’s carnivores. He educated himself in judging the quality of the meat and soon also took charge of market affairs. At the same time, he started research in his own lab to develop antisera against all kinds of snake venom with the intention of getting his PhD at the Dutch University of Leiden.

War in the former Dutch Indies

Meanwhile in Europe, the second World War had started in 1940. The Dutch Indies soon followed and were occupied by Japanese forces in 1942. In principle, everyone who held a Dutch passport was transported to prison camps. However, my grandparents and the children were allowed to stay outside of the camps. Mostly because the Japanese forces needed his expertise to treat soldiers bitten by snakes, which occurred frequently. And in spite of him also being a Military Sergeant for the Royal Dutch Indies Army Infantry in Bangkinang.

My grandfather decided to see if he could somehow use his position. There are different stories about what actually happened, but what is certain is that he ventured into smuggling to support the resistance. Meat from the butcheries to feed fighters and civilians. Or weapons for the insurgency, hidden in the cages of the most ferocious predators in the zoo. Or money and jewelry. Or perhaps he did it all.

The family’s fortunate circumstances didn’t last. In the course of 1943, my grandfather was separated from the family and taken to a men’s camp. While in captivity, he was ordered to manage medication supplies and administer medicines to Japanese soldiers who had fallen ill. Secretly, he also handed out medication to fellow captives. Unfortunately, the Japanese prison authorities caught him and decided to punish him by assigning the status of political prisoner. This subjected him to a more severe prison regime in a restricted part of Pajacombo prison, where the cells were smaller and had no or only limited daylight.

When my grandfather was taken away, my grandmother knew the soldiers would come for her too and tried to flee. But running with four small children of 4, 3, 2 and 1 years old while pregnant turned out quite impossible. They were captured and transported first to prison “De Boei” in Padang, where she gave birth. Then, they were taken north to the Bangkinang prison camp where they were held until the end of the war.

They survived. My grandfather did not. He died of malnutrition, torture and disease on the 1st of June 1945, 34 years old. Only 3 months before the end of the war in Asia. His dear friend Fred Frietman, who had been imprisoned with him, survived. He went to look for my grandmother to tell her of my grandfather’s fate and to give her the wedding ring of her beloved husband. Sadly, Fred Frietman died not long after as a result of the torture he had endured in prison.

Impossible choices

My grandfather wasn’t the kind of man who could stand by and watch. Wherever he was, he tried to do what he believed in and to find a way to fight for what he valued. Even though he must have been aware of the risks to himself and his loved ones.

Did he make the right choices? Was he a hero for trying to make a difference in the war? Or was he a terrible man for endangering his wife and children? Does it make a difference that my grandmother knew of the smuggling and supported him? Does it make a difference that she and the children survived?

Sometimes we have to determine what we want without ever being able to know what the right choice would be. Without being able to oversee the outcomes. We have to find a way to decide what we want and be courageous in pushing through even though the journey ahead is uncertain. And we have to live with the consequences of the choices we make …

Epilogue

After WW-II, my grandmother and the children lived in Jakarta before moving to the Netherlands in the early 1950s. She remarried. The children – my mother, 2 aunts and 2 uncles – all grew up to raise their own families.

Although she sometimes spoke of the times at the zoo, my grandmother never really looked back. She never again visited the area where she had lived so happily with my grandfather and where their lives had unfolded in such an unfortunate way. She moved on. For herself. For the children …

In 2005, I had a chance to visit Sumatra. Fort de Kock is now called Bukittinggi, which means high hill in Indonesian. The zoo was still there, as were the house, the remnants of the old fortress and the rose garden my grandmother had loved so much. The zoo and fortress were being renovated into a lovely integrated park with a footbridge connecting the hills.

Pajacombo is now Payakumbu. Its prison was already a prison in colonial times. It’s a sturdy old stone building, with a thick wooden bolted door dominating the front facade. It’s built in the characteristic Minangkabau style with a roof like the horns of a buffalo. In 2005, it was used as a closed facility for people with severe mental illnesses who had been convicted of crimes.

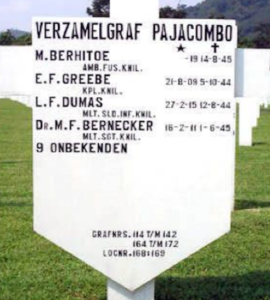

My grandfather was initially buried at a cemetery close to the Payakumbu prison grounds. In the 1960s, his remains were excavated as part of a major project to rebury many of the 25,000 Dutch victims of war in Indonesia. He now rests with fellow Payakumbu captives in a small mass grave on the Dutch War Cemetery Leuwigajah, close to Bandung on the island of Java.